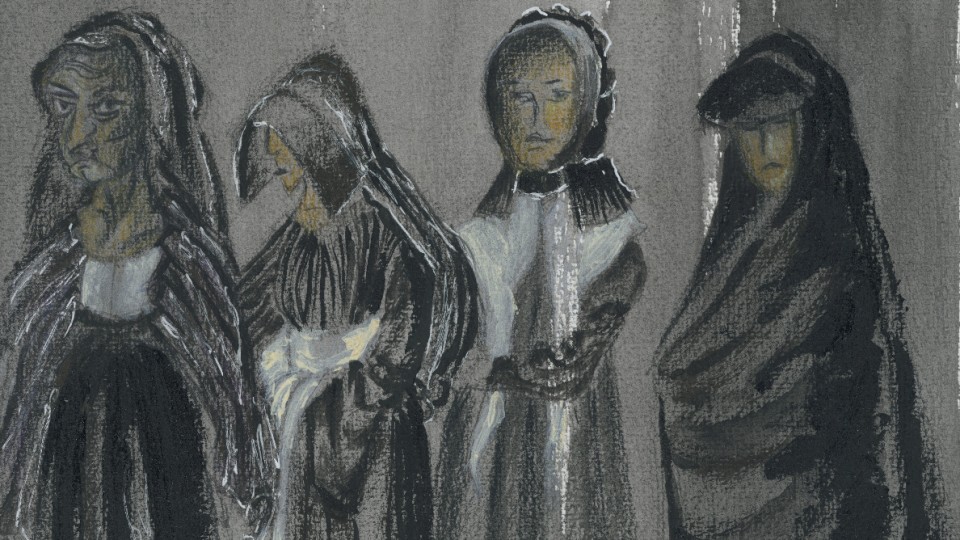

THE DEVIL'S BATH depicts 18th century life in the countryside: a cold, harsh existence marked by hardship which is reflected

in the few colours and materials of people’s garments. Tanja Hausner's costume art begins in this simplicity, finding the

essence of her figures in the finest nuances and a wide range of fabrics, interweaving past and present to create a subtle

dialogue between the forbidding nature and the painterly intensity of the images. A conversation with TANJA HAUSNER, who was awarded the European Excellence Award 2024 in European Costume Design for this work.

When is it, during the process of making a film, that you become involved in the project?

TANJA HAUSNER: When I have worked together with directors over a long period, my involvement in the project starts at an early stage. I really

appreciate an early exchange of ideas, because it gives me the opportunity to immerse myself properly in the task. I got a

few cues from Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala, then they let me work alone, eager to see what comes out. After that, there’s

the opportunity for an exchange of ideas. When I came onboard with THE DEVIL'S BATH the pandemic was still raging, and I had

a lot of time to research and think about it.

THE DEVIL'S BATH is a film about the conditions of poor peasants in the 17th and 18th centuries. Did you start out with the

materials?

TANJA HAUSNER: Materials were an important point, first and foremost linen and wool, and then there’s the question of what working people

wore at that time. It had to be materials available at the time, and it had to be functional. For example, I thought about

the women's work aprons, starting from the typical flashy blue of the work clothes and transferred it to that time, when they

have faded and got a certain patina. The fishermen's outfits were a particular issue. The rubber boots and aprons they use

today didn’t exist. I thought of aprons and boots made of very thick leather, which are water-repellent in a way. And scratchy

sweaters, which make the whole thing even more uncomfortable.

The film has a strong autumnal colour concept. How did you deal with this reduced colour palette?

TANJA HAUSNER: I definitely didn't want it all to have the typical historical patina that makes everything slightly brownish. That's why

I introduced this blue, a colour that you don't necessarily associate with a historical film, more with workwear. That enabled

me to achieve a generally valid effect going beyond the historical. The challenge with colours is to make them natural and

painterly at the same time. For all the dirt, there should also be some kind of beauty.

THE DEVIL'S BATH is set in poor circumstances, when people probably just wore one everyday garment. When everything is so

frugal, how can individuality be expressed?

TANJA HAUSNER: I'm a fan of reduction and sharp contours. I always think it's good when a character wears one meaningful costume that clearly

defines the silhouette and era of that character. It's important to me that a character is always clearly contoured, so I

like it when a character isn't dressed differently every day. That also makes it easier to give each character a singular

aspect.

How did you dress Wolf, Agnes's husband?

TANJA HAUSNER: It was interesting to put Wolf in his thick sweater. That gave him a certain power. For the pants, we found very old, worn-out

lederhosen in a store, which we often had to patch up while we were shooting. The idea of the sweater goes back to an old

picture that amazed me, because I associated the 16th/17th century more with jackets. When I discovered a sweater in the picture,

it seemed like a modern idea. The sweater as an identifying garment distinguishes Wolf from everyone else. The model was a

chainmail-like sweater, which wasn’t so easy to achieve in terms of the knitting. That gave him an old-fashioned feel, while

at the same time it was a bit comfy – after all, Wolf is a lovable guy who gets caught up in all this machinery himself.

What about the costume of the main character, Agnes? During the course of the film she wears three different outfits. Is there

some sort of development going on here? What was the idea behind that?

TANJA HAUSNER: At first she wears a quite self-confident sweater. I work with a knitter who can knit modern, graphically drawn sweaters from

great wool. I thought combining that with the linen skirt was harmonious; this wool gives it something old-fashioned, while

the unwaisted cut of the sweater has an almost modern feel. The jacket with the collar can be seen very well in the still

from the film, where she has the thread through the back of her neck. The original part is from a second-hand store; we reworked

it and put a hairy collar on it. The brown lambskin jacket was her over-jacket. It was in very bad condition at the first

fitting and required ongoing treatment.

At a certain point in the development process, costume design seems to become a major logistical undertaking.

TANJA HAUSNER: Yes, especially when the number of extras is constantly increasing. At some point you have to start improvising. There were

about 200 to 250 extras in THE DEVIL'S BATH, including children. And you need a bigger collection than that for all of them.

Things don’t always fit. That's why it's very important to me that the extras come for a fitting once before the shoot, so

there’s still a little leeway for changes. If the extras are only scheduled to turn up for the day of the shoot, you have

to find solutions very quickly. At certain moments, it is a large logistical apparatus, and it has to work. But at the same

time, the artistic aspiration in my work is definitely in the foreground for me.

In addition to the hard everyday work, there are two ceremonial moments in THE DEVIL'S BATH: the wedding and the execution.

What possibilities did a young woman from Agnes' circumstances have to design a festive dress for herself?

TANJA HAUSNER: It was clear that in the case of Agnes, the wedding dress didn’t have to be white. I thought of using blue here too, to emphasize

the special aspect. In terms of cut, I was more inspired by medieval sources, so instead of a waist and bodice, it would be

a slim dress that is slightly flared at the bottom. And I’d had some old pale velvet for decades, which I wanted to use at

some point. I thought I could make a sort of bodice as a decorative item that might have been passed down through several

generations. And then we embroidered a little bird on it as something special for the ceremony, so although there’s no white

veil, the embroidery sort of dots the i.

What was the inspiration for the bonnet that her mother-in-law puts on her head on the wedding day?

TANJA HAUSNER: We didn't want a headscarf tied under the chin in the classic way, because it's unflattering, it covers the face, and when

it’s tied back in an old-fashioned way, it looks too much like a historical film. So we copied the way of tying a scarf used

after the war by the Trümmerfrauen (the “rubble women”). Maybe that's how it was worn back then. Possibly not.

The headgear was mainly for functional reasons. When Agnes gets married, and her mother-in-law puts the bonnet on her and

ties her apron, she becomes a working woman. I constructed the apron in such a way that it was tied at the neck, to make it

clear that she is now a bound woman, a prisoner.

At the execution she wears a delicate white dress, more like a wedding dress, and she’s wrapped in a black animal skin when

she’s transported to the execution site. What can you tell us about that?

TANJA HAUSNER: At that moment, she is no longer wearing her own clothes. White was a good choice because the blood stands out very well

on the light fabric, but of course white also represents her innocence. At the moment of execution, she freed herself from

all guilt and toil. The black animal skin she’s wrapped in was a great, gruesome idea of Veronika and Severin’s; it creates

an eerie contrast to the thin white dress. For the shot after the execution of another woman, which you see right at the beginning

of the film, I’d have liked to do a little more with dye and red tulle, to work this colour into the fabric in a painterly

way, because in my opinion it also represents a nightmare image, a strong vision, and therefore it has something artificial

about it.

Looking back, what made the project so extraordinary?

TANJA HAUSNER: One challenge was to document a life consisting of a lot of work and subjugation through clothing. And to tell a story that

is clearly set in the 18th century but goes beyond that, saying something that could be universally valid. I think it’s important

to enable audiences to experience, to empathize, by not just putting characters in historical costumes but also making them

approachable and human, so you can imagine their actions today. Peasant costumes are tricky. You have to work very precisely

so the overall image fits well, so people are brought to life and don’t just look as if they’ve been "created".

Where are the most beautiful moments in a development process?

TANJA HAUSNER: When you gather together the first ideas and try to build up your own visual world, collect images and set off in search of

material. It's also important to see how a theme has been handled before and think about that, so you can create something

new that stands out. I like the exchange with directors and actors. I also find the fittings incredibly exciting. Often you

have an idea in your head, but when it’s on the human body, it doesn't work that way. Each fitting always brings us further.

Costume isn’t just manual teamwork; it's also mental teamwork. Basically, the first question is whether a costume is an option

at all. Some of them you put on and have to take off right away. But once a costume looks good, then I also have to think

about whether it feels good.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

November 2024

Translation: Charles Osborne